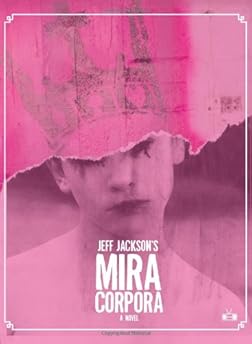

Burroughs and Dennis Cooper, behold the feral teen utopia. There is a delicate care to the prose, like that of a highly sensitive precocious child.īeyond the prose is the world, the demi-monde on which Jackson lifts the veil, and its inhabitants. It feels like the prose of the best science fiction novels, but it’s not science fiction. It’s exact and precise, naturalistic almost. The thing that is so special about Jeff Jackson’s prose is almost indescribable. I’m a sucker for the demi-monde he navigates. We soon became Facebook friends-which is somewhere on the spectrum of actual friendship-and when I discovered he had more fiction for me to engage, and that it was material excluded from the novel Mira Corpora, I jumped on the chance to read it. I first met Jeff Jackson at a reading after I had devoured his first novel, Mira Corpora (Two Dollar Radio, 2014). In the novella Novi Sad by Jeff Jackson, it is a place for wild feral youth to make a home for themselves. (3) Imaginary place.” Novi Sad is a place with a resonance across time, a place of sorrow and atrocity, a place like and unlike any other.

Although the city lends a title to Jeff Jackson’s book, it does so, as he says in the Author’s Note because “Our stories, which I’ve smothered for so many years, make sense transposed on this immolated terrain.” There is also an epigraph to the book by way of definition: “ Novi Sad (1) ‘New plant.’ (2) Serbian city that has been devastated multiple times, most recently during the Kosovo War when it was bombed into annihilation, bridges destroyed, communications severed, water supply polluted.

Childhood understanding in the face of horror, emptiness, and banality is also the territory of American writer, Jeff Jackson in his new novella, Novi Sad (Kiddiepunk, 2016). The brilliance of Kiš is that he connects an event like this with childhood and somehow further illustrates the emptiness and banality of nationalist sentiments. When Kiš describes his understanding of nationalism as a child, like some petty us versus them game, he notes: “the bloody massacre of January 1942, the infamous ‘cold days’ of Novi Sad, when the cruel children’s game would end tragically for so many beneath the ice of the Danube.”

Due to the current political climate in the United States, I was recently rereading Danilo Kiš’s essay, “The Gingerbread Heart, or Nationalism,” in which he begins by reminding us that “Nationalism is first and foremost paranoia, individual and collective paranoia.” As Kiš moves along he elucidates further on the subject: “Nationalism is the ideology of banality… Nationalism is also kitsch…” On this reread, somewhere in the middle of the essay, I was struck by a parenthetical reference.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)